The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Topics

Regions

Current geopolitical competition has deepened into a Second Cold War between US and China, but this is no longer a fight over territory but rather control of global networks – with increased state-led attempts to control semiconductor supply chains and electric vehicle (EV) production to digital platforms, transport infrastructure, and financial payment systems. How can the global South and social movements navigate this new geopolitical terrain?

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

From containment to connectivity: the emergence of state-capitalist geopolitics

In 1944, as the end of World War II was in sight and Allied victory seemed imminent, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin met in Moscow to divide the post-war world. They had more in common than either would have liked to admit. Both relished the geopolitical wrangling and cloak-and-dagger intrigue that characterised their first face-to-face meeting. They agreed upon the percentage of control each would exercise over various countries following the war – the Soviet Union (USSR) got 90% of influence in Romania and Britain 90% in Greece, while Hungary and Yugoslavia were split 50:50. This informal agreement was later finalised at the Yalta Conference when the two met with US President Roosevelt, establishing the foundation of the post-war global order.

Any pretence of post-war cooperation among the former allies ended abruptly with the onset of the Korean War. As the Cold War set in, the spheres of influence agreed at Yalta hardened into territorial blocs. Cold War geopolitics in the following decades amounted to a renegotiation of the Yalta agreement as both the US and the USSR sought to expand their blocs. The containment of communist influence became the cornerstone of US geopolitical strategy for fear that if one country became communist, neighbouring countries could ‘fall’ like dominos in quick succession. The Soviets sought to forestall ‘capitalist encirclement’ by inhibiting the expansion of the US alliance system. Both countries courted newly decolonised countries as prospective members of their respective blocs.

By the 1980s, the strategic landscape had shifted dramatically. The USSR lagged behind the US in technological development, economic prospects, and international influence. Gorbachev’s ambitious reform agenda to address these problems ultimately destabilised the Communist Party, leading to the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, leaving the US as the world’s sole superpower. Under President Clinton, Washington expanded the scale and scope of the international institutions that integrated the former West bloc. This global neoliberal project constituted a maximalist agenda of economic, trade, and financial liberalisation alongside the insulation of markets from democratic politics. This new era saw multinational corporations (MNCs), mainly from the US, Europe and Japan, move production overseas, where labour was disempowered and cheap. They also outsourced to local producers, creating complex, multi-stage production networks that were truly global in scope.

US policymakers believed that economic interdependence would reduce conflict, as states could not afford the cost of being ostracised from a globally connected economy. Countries that remained disconnected from the global networks were seen as threats to the US-led international order because they could not be subject to market discipline, which explains why Washington’s primary strategic imperative was to integrate people, countries, and regions into the global economy by force if necessary.

Scholars referred to this as neoliberal geopolitics: ‘[D]anger is no longer imagined as something that should be contained at a disconnected distance. Now, by way of complete counterpoint, danger is itself being defined as disconnection from the global system’. Many countries forged connections with global networks under duress. International financial institutions imposed economic structural adjustment programmes to reduce barriers to capital mobility, while states like Cuba, Iran, and Libya endured US or international sanctions. At the same time, the US-led invasion of Iraq demonstrated that the US was willing to use hard power to expand global networks. The US-led Coalition Provisional Authority passed 100 administrative orders in its first 14 months, comprehensively liberalising Iraq’s battered economy.

Cracks in this system began appearing early in the 2000s, as the project of neoliberal globalisation was buffeted by a series of political and economic crises, and the so-called Washington Consensus descended into failure and acrimony. Trade and investment liberalisation stalled as the World Trade Organization (WTO) Doha Round negotiations failed in 2001 as governments in lower-income countries (confronting social pressures) were no longer willing to accept the promise that liberalising trade would ‘lift all boats’. The 1997 Asian financial crisis also bred reluctance to pursue financial liberalisation, and a ‘pink tide’ swept left-leaning governments into power across Latin America. The 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) further eroded confidence in the neoliberal model. In its aftermath, the US and China provided the ballast that kept the global economy upright, deploying decisive statist measures to maintain global liquidity and investment in the real economy.

The financial crisis also set in motion the return of Great Power competition, as it revealed fault lines in the US-led international economic order. Beijing’s assertive response and extensive intellectual property theft further alienated MNCs that had invested significantly in China. The US response was twofold. Geopolitically, it signalled its preparedness to use hard power to contain China’s growing naval power in the South China Sea while simultaneously pursuing deeper economic integration. The Obama administration’s flagship initiative, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, remained wedded to neoliberal geopolitical practices. While the trade agreement sought integration of Asia-Pacific economies, it conditionally excluded China – offering inclusion only if Beijing dismantled its statist economy (an impossible demand).

The Trump administration, however, marked a decisive break with the policy of engaging China, with the 2017 US National Security Strategy officially defining China and Russia as adversaries. It was the first time in more than two decades that ‘hostile states’ – rather than non-state terrorist groups – were identified as the primary threat to the US, and it buried the assumption that economic engagement could turn rivals into partners. As the 2017 US National Security Strategy puts it:

These competitions require the United States to rethink the policies of the past two decades—policies based on the assumption that engagement with rivals and their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners. For the most part, this premise turned out to be false.

China responded to the Trump administration’s provocations with increasingly comprehensive preparations to reduce its technological and economic dependence on the US by increasing state control of key industries and banking and focusing on strategic high-technology sectors.

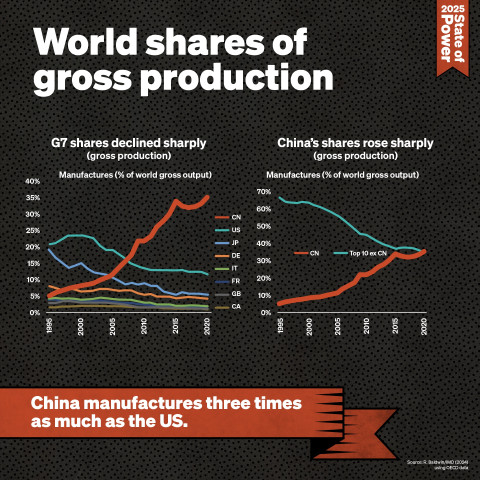

Current geopolitical competition has deepened into a Second Cold War – an entrenched and society-wide conflict with little prospect of swift resolution. Yet, unlike the first Cold War, the US cannot hope to territorially ‘contain’ China today, which is indispensable to the global economy – in 2024, for example, it accounted for nearly 35% of global manufacturing. But with the US ruling out further economic engagement, a novel strategic orientation is required. The new battleground revolves around the control of global networks – from semiconductor supply chains and electric vehicle (EV) production to digital platforms, transport infrastructure, and financial payment systems. Control over these transnational networks offers the prospect of wielding power well into the current century.

The US, China, and regional powers are expanding their role as economic actors as they compete to define the geography of these networks, establish rules of participation, erect barriers of entry to opponents, and control their most strategic nodes. We refer to this as state-capitalist geopolitics.

The new era of state-capitalist geopolitics

State-capitalist geopolitics operates not as a coherent doctrine but as an evolving set of practices. As the world adjusts to a new phase of geopolitical rivalry in the context of deep interconnection that precludes containment or connection as singular viable options, states are driven to devise new strategies to play power politics. This, of course, does not mean that territorialised geopolitics and military doctrine are no longer important, as Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza and Lebanon make painfully clear. The role of the US in fuelling these conflicts, its increasing inability or unwillingness to manage others, and the growing weight of middle powers, have collectively driven a marked increase in interstate violence during recent decades. But, as we shall illustrate, the structure of the economy is such that it nevertheless de facto forces much geopolitical competition to take a new, network-centred form.

State-capitalist geopolitics also involves a drastic expansion and reconfiguration of states’ roles as industrial policy actors, as tech and innovation catalysts, controllers of key financial nodes and infrastructure, financiers of national champions and strategic sectors, investor-shareholders, and direct owners of capital and assets. Thus, in addition to trade tariffs, foreign investment restrictions, export controls, financial sanctions, and other defensive or offensive economic measures, the signature forms of state-capitalist geopolitics also include things like new forms of techno-industrial policies, SWFs, policy banks, state enterprises, state-owned venture-capital funds, and other state-controlled corporate entities.2

More than simply fostering investment and growth, these policy instruments and vehicles afford states the capacity to exercise different degrees of ownership and control over capital and assets, from full state ownership to governments owning majority or minority equity positions, using golden shares to retain veto rights, or acting as passive investors. They also allow them to forge new state-capital alliances geared towards achieving geostrategic objectives. In sum, what makes state-capitalist geopolitics a distinct and qualitatively different mode of geopolitical practice is both its fundamental logic (shaping and exerting control over the networks that underpin globalisation, controlling their most strategic nodes) and its tools and signature forms (the extensive mobilisation of muscular state economic interventionism and revamped state ownership).

To understand why states across the globe increasingly practise state-capitalist geopolitics, we must look at the historical development of global capitalism over the past two decades. What scholars refer to as ‘new state capitalism’ has deep roots. At least four factors have driven its dramatic global rise. First, financial crises have played a decisive role in developing new forms of interventionism and state ownership. The financialisation of capitalism means that shocks reverberate more rapidly through the global credit system (the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, triggered a massive financial shock that plunged many low- and middle-income countries into debt crises).

Governments have had to adapt to this context of heightened vulnerability, providing massive rescue plans, bank recapitalisations, and counter-cyclical investments in the wake of financial crises, while central banks in high- and lower-income countries have developed instruments to stabilise financial markets and ensure they function properly. For instance, the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet virtually doubled in size (relative to GDP) in response to the Covid-19 crisis.

Second, the industrial restructuring of the world economy and the formation of increasingly complex global value chains have pushed states towards muscular interventions to secure the ‘competitiveness’ of their economies. Hence, the revival over the last decade of development planning, industrial policies, and large-scale state-coordinated investment (often conducted by state enterprises, SWFs, or development banks) in energy grids, digital networks, transport infrastructure, and integrated logistics systems.

Moreover, the accumulation of vast surpluses – resulting, for instance, from the consolidation of export-oriented models in East and Southeast Asian economies and the ‘re-primarisation’ of many Latin American and African economies – have fuelled the multiplication of SWFs and the spectacular growth of their global asset control. Sovereign funds have expanded their operations at home and abroad since the early 2000s, occasionally in partnership with state enterprises. As of 2024, there were 179 sovereign funds globally, which is a more than sevenfold increase since 2000. They control vast amounts of money and capital (worth more than $12.4 trillion) and have become major actors in global financial markets. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that state enterprises now account for 20 percent of the world’s 2000 largest firms, which is twice as many as twenty years ago.

Third, slowing rates of global economic growth – if not outright stagnation in some countries – have intensified competition for market share and access to strategic assets and investment opportunities across industrial sectors, from agro-chemicals to shipbuilding, aluminium, steel, coal power, solar panels, 5G technology, and more. In response, governments are implementing policies to support the international competitiveness of their companies and assist firms in developing or acquiring strategic capabilities at the cutting-edge of the technology and productivity frontier, such as advanced semiconductors, nanotechnologies, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, 5G, the Internet of Things, cloud computing, and intelligent robotics, among others.

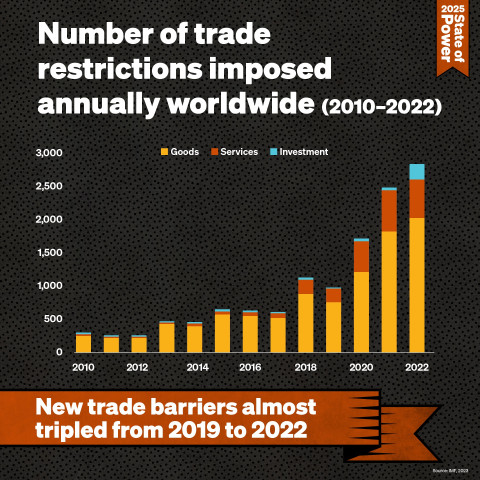

Ambitious industrial policies include state subsidies, and the growing mobilisation of policy banks and state-owned investment funds to inject liquidity in the form of investment or subsidised credit. States have also ramped up trade and investment restrictions and occasionally injected state property (in the form of equity stakes) into key firms to protect critical supply chains from foreign competition, such as in the semiconductors and EV batteries sector. The US, for instance, has imposed 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs, while the EU has imposed import duties of 38.1%.

Source: IMF, 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/08/28/the-high-cost-of-global-economic-fragmentation

Fourth, this context led to the development of virulent forms of economic nationalism that collapse the distinction between economic interest and national security. As the definition of national security has expanded, economic competitors are portrayed as threats to the sovereignty and integrity of the nation. To establish control over strategic sectors, renewed economic nationalism does not hesitate to mobilise state ownership through, for example, shareholdings by investment funds and state-owned companies.

Nor does it hesitate to deploy trade sanctions to penalise foreign competitors on often questionable grounds. The aforementioned EU customs duties on imported Chinese EVs illustrate this trend. These varieties of economic nationalism often have troubling undertones, mixing economic protectionism with xenophobia and racial prejudice. The mobilisation of state power to discipline foreign competitors in the name of national security is often intimately connected – discursively, ideologically, and materially – with the development of coercive and repressive forms of domestic rule around the globe.

In sum, capitalist crises, contradictions, and competitive dynamics have created the conditions for a drastic expansion of state ownership and a concomitant proliferation of muscular modalities of state interventionism.

State-capitalist geopolitics are reshaping globalisation

As the Second Cold War has intensified over the past few years, powerful states have increasingly marshalled these new state capitalist tools for geopolitical ends. This is not triggering a process of ‘deglobalisation’ – that is a reduction in global flows of finance, trade, and services. Rather, in most cases the goal is to reshape and exert control over the global economic networks that undergird globalisation. Consider, for instance, the case of infrastructure networks, where hegemons and mid-range powers compete to finance, build, and control connective infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries. Competitors in this infrastructure race have created new dedicated state-owned entities and have expanded existing ones.

Under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative, for instance, China coordinates a range of government agencies (e.g. National Development and Reform Commission), development and policy banks (e.g. China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China), states enterprises (e.g. China Railway International and China Machinery Engineering Company), and sovereign funds (e.g. Silk Road Fund and China Africa Development Fund), blending development-oriented aid, grants, and below-market interest loans, commercially oriented export credits, and market-based funding mechanisms to pursue a staggering range of global infrastructure projects.

Japan’s Policy Program for Promotion of Overseas Infrastructure Systems similarly combines the operations of multiple state-owned agencies, including the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) (official development assistance), the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (export credits), Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (trade insurance), and two state-owned infrastructure investment funds: the Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport and Urban Development and the Fund Corporation for the Overseas Development of Japan’s Information and Communication Technology.

The EU has also reconfigured its development finance architecture to better compete. The relationship between the European Investment Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, national development banks, and EU member states was repurposed to align them with the Union’s geostrategic objectives with respect to infrastructural development in lower-income countries.

Similarly, Türkiye has boosted its state support (through tax credits, Türk Eximbank finance, and patronage networks) to help Turkish construction firms establish themselves not only as leading contractors but also investors in private and public infrastructure in the Middle East, the Maghreb, and sub-Saharan Africa. Even the US, often considered relatively reluctant to engage in state-owned development banking, has extended the prerogatives and budget of the recently created US International Development Finance Corporation to compete in the infrastructure race. The US is also attempting to forge new state-capital alliances to compete internationally. The Emerging Markets Transition Debt is a case in point: a partnership between the US treasury and global asset managers that aims to channel private capital from institutional investors into clean infrastructure, clean technology, and decarbonization while, according to former US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, ‘advancing key Treasury priorities’.

State-capitalist geopolitics also increasingly play out in global production networks. This is seen in advanced manufacturing and digital sectors such as semiconductors and AI. Oil-exporting Gulf states, particularly the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, use their SWFs to invest in advanced manufacturing, software, and generative AI worldwide. They are also purchasing large quantities of high-performance semiconductors from Nvidia and other top chipmakers and offering generous pay packages to attract AI engineers and software developers from around the world (particularly from China) to support AI development efforts and ambitions.

Many advanced capitalist economies in the West and East Asia have launched ambitious techno-industrial plans to consolidate their positions in semiconductor supply chains (a means to reindustrialise, ‘reshore’ strategic production capacities, and ensure technological sovereignty). This includes the US CHIPS and Science Act, the UK’s National Semiconductor Strategy, the European Chips Act, and Korea’s K-Chips Act. Japan has announced a vast programme of subsidies to incentivise world industry leaders (TSMC, Micron, Samsung Electronics, Rapidus, and others) to invest in new production facilities in the country.

Moreover, the Japan Investment Corporation, a state-backed investment fund overseen by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, is now directly acquiring controlling interests in strategic firms, such as the Tokyo-based company JSR. This is the first time the investment fund has mobilised to effectively nationalise (albeit in a market-friendly way) a firm that controls a critical node in the global semiconductor supply chain, thereby mitigating supply chain and geopolitical risk. Likewise, the US state is currently setting up a sovereign wealth fund to inject equity and make major investments in strategic sectors and supply chains in an explicit attempt to compete with geopolitical rivals.

Cleantech and renewable energy are another set of production networks where state-capitalist geopolitics have been particularly active and contentious, with extensive mobilisation of SWFs, state-owned venture capital funds, policy banks, and state enterprises. The US IRA, the European Green Deal, and China’s vast green tech subsidy programmes underline the geopolitical stakes. Meanwhile, the NATO Innovation Fund, launched in the aftermath of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, is the world’s first multi-sovereign venture capital fund, with a mandate to invest EUR 1 billion in start-ups developing cutting-edge technology to address defence and security challenges, including ‘green tech’ and renewable energy. This suggests that state ownership may become a privileged instrument for bringing together security and ‘green’ imperatives.

Developing and emerging markets are also experimenting with state capitalist tools to engage in the geopolitics of energy transition. Brazil announced new tariffs on Chinese EVs and plans to combine capital and expertise from Petrobras (its state-run oil company) and BNDES (a central Brazilian development bank) to structure a state-backed venture capital fund for renewable energy and low-carbon mobility. A powerful state enterprise, OCP, is at the heart of Morocco’s strategy to become a leader in green hydrogen connected with Europe’s green hydrogen infrastructure. Indonesia is increasing the participation and ownership of its extensive landscape of state enterprises and state-owned development funds in the nickel sector to position itself at the heart of global steel and electric battery supply chains.

Thus, state-capitalist geopolitics are not precipitating the end of globalisation but are reshaping the global economy. Trade and capital flows remain at all-time highs. Yet these flows are increasingly reshaped and corralled by government intervention (through a mixture of ‘carrots’ and ‘sticks’) in directions that favour direct geostrategic and security objectives.

National and regional development strategies: towards polyalignment?

To the extent that it displaces neoliberal geopolitical logics, which sought to produce a liberal peace by subordinating the world economy to MNCs’ bottom lines, state-capitalist geopolitics offers potential for countries, particularly countries of the Global South, to forge new development strategies within the global political-economic order – and potentially improve their relative position within it. Two key changes are especially noteworthy.

First, MNCs’ investment and location strategies increasingly exhibit a geostrategic logic. Simply put, MNCs increasingly organise their operations with not only issues such as labour costs and customer market access in mind, but also the minimisation of geopolitical risks. Far from simply liberalising economies and courting MNCs directly, countries may capture investment by positioning themselves as secure partners by cultivating relations with superpowers. For instance, they might gain validation under initiatives like the US Chips Act’s ‘International Technology Security and Innovation’ programme or by developing ‘connectivity strategies’ to take advantage of their geostrategic assets.

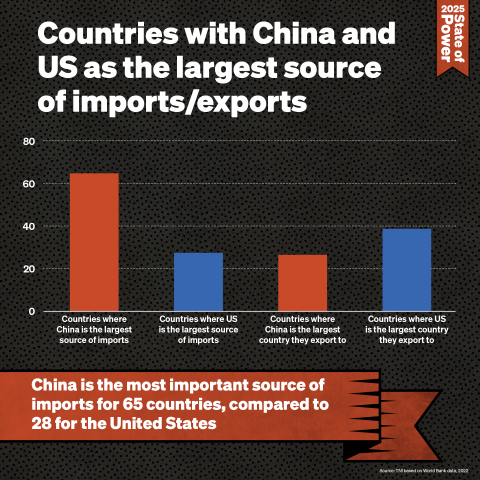

These could include location alongside trade routes, proximity to key markets, and possession of the strategic resources required for new and emerging production networks and decarbonisation projects, such as critical transition materials. Alternatively, ‘connector countries’, such as Hungary, Poland, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia, position themselves as conduits to bypass tariffs and sanctions, bridging networks across geopolitical rifts. Mexico is doing this for Chinese investment in EVs in the Americas. Meanwhile, Morocco aims to attract investment in its car-production sector from Chinese, French, German and Korean companies.

Source: TNI based on World Bank data, 2022. https://wits.worldbank.org/Default.aspx?lang=en

Moreover, greater state intervention and control enables global South countries to avoid ‘choosing sides,’ as they aim to remain connected with multiple powers such as the US, China, EU, Russia, or regional powers – a strategy referred to as ‘polyalignment’. When asked by The Economist why he ‘described Singapore’s status as being neither pro-China nor pro-America’, the Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore Lawrence Wong pithily replied: ‘We are pro-Singapore’.

State leaders across the developing world have expressed similar views and wish to develop business and political relations with multiple partners. For instance, governments in Indonesia and Vietnam hope to attract manufacturing investment from Chinese and US firms. Brazil’s polyalignment is characterised by federal, sub-national, and non-state actors pursuing diverse interests and relationships with China and Western powers, resulting in a multifaceted foreign policy that transcends traditional ideological boundaries and administration changes. Türkiye, similarly, navigates competing connectivity projects backed by rival powers, such as China’s Middle Corridor and the US-backed IMEC, while pursuing its own initiatives like the Zangezur Corridor and Iraq Development Road to maintain strategic autonomy.

The long-term effectiveness of these strategies remains to be seen. For one, the IMF warned that failure to choose sides – which it termed ‘policy uncertainty’ – could discourage foreign direct investment (FDI) because, as research has shown, this flows more readily to geopolitically aligned states. Besides, successfully ‘polyaligned’ states may still face familiar development constraints and bottlenecks, from risks of new ‘resource curses’ to relegation as an environmental ‘sacrifice zone’ and financial dependency.

Second, geopolitical deadlock has weakened disciplinary neoliberal institutions like the WTO, affording countries with fiscal and institutional capacity more policy space to pursue state-led development strategies with reduced fear of recrimination. New resource nationalisms are consequently on the rise in Southern economies. Indonesia, for example, is pursuing an industrial strategy for capturing value in the battery sector by banning the export of raw nickel to develop domestic processing capabilities. While the EU won a ruling against this practice at the WTO in 2022, the body’s frozen appellate court is unable to hear Indonesia’s appeal and thus apply any penalty. In the meantime, Indonesia’s share of global nickel extraction has soared from 5% a decade ago to 50% in 2023.

Local and regional governments also adapt alignment agendas as they reconsider prior development strategies in the face of geopolitical tension, state-capitalist practices, and geostrategic investment logics. In contrast to attempts to ‘hold down’ international capital in the neoliberal globalisation period, today’s regions cannot ignore the increasingly central role of states and their efforts to reshape MNC investment logics, including for private and hybrid firms and those they directly control.

Two types of regional development strategies are emerging from the logic of state-capitalist geopolitics. In peripheral economies not tightly aligned with either the US or China, new ‘connector regions’ are emerging. In Hungary, regions combine Russian gas with European managerial coordination and Chinese battery technology. In Vietnam, regional governments vie to capture fragments of outsourced Chinese supply chains and integrate them with US-led firms to bypass or navigate US controls.

Older industrial districts within core capitalist economies are also finding new development opportunities. For example, Magdeburg in former East Germany and Ohio in the US were, until recently, viewed as deindustrialised rustbelts struggling to attract capital investment. Today, they are sites for vast new chip-fabrication complexes at the behest of Intel. Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown claimed that Intel’s semiconductor manufacturing in the state means that we can ‘bury the term ‘Rustbelt.’ While this is unlikely, it does illustrate the relationship between domestic politics, industrial policy, and national security. Germany’s deputy chancellor Robert Habeck claimed that Intel’s investment in Magdeburg will ‘raise semiconductor production in Germany to a new level, and is an important contribution to growing European sovereignty’.

Given the scale of subsidies, such regions could not simply appeal directly to MNCs for such investments. Instead, they first position themselves to national governments as strategic investment sites – typically in terms of national social cohesion, national security, or, more crudely, the electoral strategies of governing parties. In sum, the shift to state-capitalist geopolitics presents opportunities for localities and regions not previously apparent within neoliberal geopolitics.

Strategic openings and political dilemmas for progressive forces

We now turn to lesser-examined possibilities for emancipatory social change and progressive politics in view of changing modes of power amidst state capitalist geopolitics, particularly from the perspective of labour and social movements. The conjuncture created by state-capitalist geopolitics is not an easy one for progressive social forces to navigate. To be sure, there are opportunities in both ideological and material terms. This section explores potential strategies in this new landscape to advance emancipatory social change while acknowledging the complexity of this terrain.

First, state-capitalist geopolitics have already re-politicised the role of the state as an agent of economic and social transformation, as states intervene across economies and societies in ever more explicit and visible ways. This shift undermines neoliberal institutional reforms that insulated markets from democratic politics. It is now more difficult for neoliberals and free-market ideologues to claim that states are incapable of doing meaningful things besides protecting private property rights, maintaining sound money, and waging war.

State-capitalist geopolitics thus offers opportunities for social movements to push states to use their rediscovered capacities and resources for purposes that are, at the very least, less socially and environmentally destructive in ways that (1) immediately address the worsening crises of living standards and inequity in most countries worldwide; and (2) alter the balance of forces in favour of the working class. States can act on the economy in ways that do more for their citizens, notably in redressing inequalities, building working-class power, and decarbonising their economies.

State-owned policy and development banks have again become central actors with proven track records of supporting firms, sectors, and industries deemed strategic. Their burgeoning roles inevitably provoke the question: Why not massively expand their lending capacities to steer rapid decarbonisation pathways and facilitate vast transfers of financial resources from richer to poorer countries? States also now directly or indirectly own vast amounts of assets and capital via state enterprises and SWFs, which are themselves invested in a wide range of firms and sectors.

Here, too, there is potential to force states to divest from carbon-intensive industries or to simply keep fossil fuels in the ground. This could also mean using state enterprises and assets as ‘activist shareholders’ to influence firms in which they hold shares towards less ecologically harmful practices. Moreover, if state interventionism can be mobilised to penalise foreign states and firms or to achieve control of key economic networks, then surely such state coercive capabilities can be directed towards enforcing environmental laws, labour regulations, and robust tax systems to discipline carbon-intensive capital and tame corporate power.

The path to harnessing state-capitalist geopolitics for progressive ends is not without obstacles, however. Decades of neoliberalism have eroded the liberal-democratic channels and mechanisms of representation through which progressive forces have pushed for past reformist projects. The powers of trade unions have been reduced by law and industrial restructuring, social democratic parties have embraced markets and turned away from their original roles as representatives of the interests of working people, and economic policymaking has become increasingly disconnected from citizens’ everyday needs.

In this context, it is difficult, though not impossible, to push for a ‘greener’ and ‘more democratic’ form of state capitalism via conventional, parliamentary channels. In a way, we remain (at least partially) stuck in the neoliberal institutional straitjacket, even as neoliberal ideology may be losing ground. Furthermore, new state capitalism is increasingly enmeshed with repressive state apparatuses geared towards suppressing popular dissent, broad-based mobilisation, and other protests and demonstrations. This overlap of new state capitalism with authoritarian tendencies complicates efforts to extract its potentially progressive elements. This challenge is further exacerbated by the aggressive geopolitical and economic-nationalist stances often accompanying state capitalism, where elites increasingly portray competition over globalised economic networks as a zero-sum game.

To navigate these challenges and opportunities, we point to several areas of inquiry and possible openings. Building transnational solidarity, reframing key concepts like security and development, and leveraging the expanded role of the state offer some possibilities to achieve a more equitable future. Industrial policy has taken centre stage in the current geopolitical conjuncture. There is potential to, for example, advocate for green industrial strategies centred on decarbonisation or tie state subsidies and investments to community benefits and labour rights. The current period also offers the opportunity to re-prioritise alternatives to neoliberal economic models, such as cooperatives, solidarity economy initiatives, and universal public services. Given the network orientations of state-capitalist geopolitics, there is a continuing need for transnational solidarity. Finally, as ‘first’ and ‘third’ world neoliberalism varied, the potential for progressive forces under state-capitalist geopolitics requires context-based social policies and regional green deals. In the face of increased competition, cross-regional solidarity can help resist divide-and-conquer tactics.

A platform to harness the powers of state capitalism for progressive ends must categorically refuse to accept that gains for workers and citizens in one country are made at the expense of populations and the natural environment elsewhere. This calls for new forms of planetary solidarity as a guiding principle for our project to repurpose the state, the assets it owns, and its planning powers.

Nevertheless, articulating cogent and meaningful internationalist politics is particularly difficult at the current historical juncture. The structures and effects produced by state-capitalist geopolitics tend to foster a climate propitious for inter-imperial chauvinism, in which top-down narratives that collapse the distinction between economic interest and national security, and explicitly adopt rhetoric that portrays economic competitors as threats to national integrity, are particularly ‘sticky’. We must reject these ideas, discourses, and worldviews and prevent them from becoming accepted as ‘common sense’. This may require articulating alternative visions of public ownership and ecological planning for shared prosperity within and across national-territorial borders.

Seizing opportunities while overcoming obstacles will necessitate creative strategies of engagement within and beyond the realms of institutional politics, forging new transnational popular alliances, and producing counter-hegemonic and compelling alternative visions for a just and sustainable future.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Publication date:

-

AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

Can China challenge the US empire?

Publication date:

-

China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Publication date:

-

Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: