The Fabric of Convergence Reflections from the Nyéléni Global Forum

Temas

In what ways can food sovereignty or agroecology act as a viable joint framing for systemic convergence? The third Nyéléni Global Forum in Kandy, Sri Lanka, brought together over 700 activists with the aim of weaving convergence and strengthening alliances between food sovereignty and social justice movements. The authors reflect on their experience at the Forum, highlighting successes in cross-movement collaboration as well as frictions in organising, representation, and frameworks. Looking ahead, the Kandy Declaration calls for actions to deepen dialogue, transform governance, and build collective capacity to advance systemic transformation.

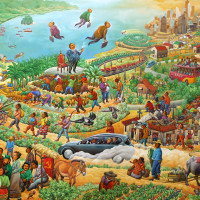

Nyéléni Global Forum/Creative Commons

Introduction

In September 2025, we travelled to Kandy, Sri Lanka, along with more than 700 other activists from more than 100 countries and Indigenous Territories, to attend the 3rd Nyéléni Global Forum. ‘Nyéléni’ is the name of a woman farmer from Mali. To recognise and honour her strength, her name was given to the first Food Sovereignty Forum held in Mali in 2007, in which global food producer movements collectively articulated the six pillars of food sovereignty. The name was carried forward to the second Global Forum in 2015 where participants advanced strategies for promoting agroecology and defending it from co-optation.

Under the slogan “Systemic Transformation Now and Forever!”, the main objective of the 3rd Nyéléni Global Forum was to build convergence. The food sovereignty movement, as a movement of movements coordinated by the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty, is already diverse, bringing together peasants, fisherfolk, food and agricultural workers, pastoralists, Indigenous Peoples, feminists, grassroots environmentalists, migrants, urban poor, Community Support Agricultural initiatives (CSAs) and consumers. This time, the aim was to strengthen alliances between the food sovereignty movement and other global social movements in recognition of the fact that transforming the food system requires wider, system-level change in the fight for global justice.

We participated in the Forum as delegates of the Europe and Central Asia region (ECA), representing the Human Rights Defenders (FIAN International), NGOs (TNI) and Research (Scholar Activist) constituencies. In this piece, we put forward our personal reflections on the process of convergence building. We explore successes, challenges and share critical questions that emerged, for us, out of the Forum.

Convergence for systemic transformation

The 2025 Forum was organized around delegations from six world regions1 and over 8 global movements.2 Participants represented movements of small-scale food producers such as peasants, fisherfolk and pastoralists as well as Indigenous Peoples, and movements dedicated to public health, the social and solidarity economy, climate and environmental justice, labour organising, women’s rights and the rights of migrants and refugees.

To start to bring these diverse movements together around specific goals, five priority areas for convergence were identified in the process leading to Nyéléni 2025:

- Democracy, peace, and international solidarity.

- Peoples’ health (health for all)

- Climate justice and energy sovereignty

- People’s economy

- Land, territory and agrarian reform

Preparatory consultations were organized within the regions and global movements to build a Common Political Action Agenda (CPAA) to address inequitable economic systems marked by corporate concentration and the exploitation of people and nature, crises of democracy, new forms of colonialism, and the climate crises. The overarching goal of the CPAA is to design a roadmap for achieving people’s power and transforming the dominant capitalist, patriarchal, imperialist, colonialist, racist, caste-ist and supremacist system.

The Nyéléni Global Forum thus opened with the objective of collectively building a Political Declaration and fine-tuning the CPAA. This attempt at holding together the fight against capitalism, patriarchy, racism, imperialism and all forms of oppression was welcomed by many. It introduced a shift in how the food sovereignty movement had organised in the past, which focused primarily on the fight against capitalism and neoliberalism. It disrupted, even if in subtle ways, more familiar modes of movement building through an explicit focus on care, diversities and political facilitation. A Gender and Sexual Diversities and Allies Assembly was organised which, for the first time, visibilised the contribution of and challenges faced by the LGBTQIA+ community in the food sovereignty movement. There was also an explicit commitment to a politics of care, with Respect and Diversity Guidelines and a Code of Conduct for Creating a Safe, Inclusive and Respectful Forum for All developed. A care team mobilized to facilitate and ensure respectful engagements throughout the Forum.

Nyéléni Global Forum/Creative Commons

Convergence Successes

The process of convergence was successful in many ways. First, the dialogue with movements for people’s health and social and solidarity economy was fruitful and enabled the articulation of new proposals. While the food sovereignty movement has a long and well-established stance against trade liberalisation and the WTO, participants developed concrete and prefigurative alternative trade and economic justice agendas in the areas of feminist economics, care and social reproduction, mutual aid, territorial wealth building, and circularity. Similarly, participants creatively articulated new links between the public health and food agendas, both in terms of solutions and diagnosis, for example around pesticides, menstrual health and access to toilets.

Second, the Forum fostered dialogues around the potential of rights-based frameworks for mobilizing and building convergence across movements. Participants discussed risks to multilateralism, the broader crises of democracy, growing threats to civil society mobilization, the intensification of wars and conflict and the urgent role of international solidarity (including, most critically, in relation to the genocide in Palestine but also in other places), and new forms of colonialism, including over land and technology.

Third, the Forum insisted on the power of agroecology as a solution to the climate crisis and rejected false climate solutions. Participants discussed emerging threats and how to develop structural responses to these. New climate-related challenges include carbon and biodiversity credit projects, land grabs for critical minerals/the green transition leading to a new wave of climate extractivism, the digitalisation of agriculture, and the need to move beyond the fossil fuel economy. These new threats require more research and coordinated advocacy work across new policy arenas. Some activists pointed to a need for enhanced collaboration between social movements and researchers to identify future developments and shape resistance strategies, especially in the areas of energy sovereignty, technology sovereignty and digital and data justice.

Finally, the Forum led to the identification of shared global campaigns — including on an alternative trade framework based on food sovereignty, against industrial aquaculture and fishing, on abolishing illegitimate debt – even if there was little time to discuss collective strategies for advancing these.

Nyéléni Global Forum / Creative Commons

Convergence frictions

Movements all have their unique histories, experiences and ways of organizing. This can complicate efforts at convergence. We noted several factors that made convergence hard to facilitate and pose questions around if, when, and how convergence can best happen.

First, we are experiencing a period of unprecedented geopolitical chaos, wars and militarization and rapid reconfiguration of what social change means. This means that the need for food sovereignty movements to regroup and consolidate existing efforts, take stock of, and assess options for global mobilisation co-existed with the need to open-up to the possibility of forging new alliances. Questions for further reflection include:

- What are the risks and benefits of convergence at this moment in time?

- How to ensure that institutions of global governance, especially across the UN, can be defended and reformed to reinforce participatory governance mechanisms, legitimate multilateralism and a strengthening of the global human rights regime?

- How should the movement navigate the uneven appetite for, or perceived urgency of convergence building in and across different regional and national contexts?

Second, bringing new actors together required a considerable investment in explaining and recalling the food sovereignty movement’s history and objectives. This took energy and time away from co-shaping joint futures, collective actions and identifying and building convergence spaces. It also took time away from the more joyful and embodied modes of movement building. Some key questions that deserve more examination include:

- Should convergence be coordinated by existing food sovereignty movement structures or do new structures need to be co-created across all movements?

- How formal, flexible or institutionally anchored should these coordination mechanisms be?

Third, the extent to which food sovereignty and agroecology can bind different movements together for systemic transformation is still untested. Agroecology, which received a lot of attention at the Forum (including through the participation of philanthropists involved in agroecology funding) provided an interesting framework for convergence (around health and care especially) but also showed its limits. Its focus on the land and on crop-based, closed systems, risks marginalizing the perspectives, contributions and agency of key food system actors like fishers, pastoralists, and some Indigenous Peoples living in territories unsuited for agroecological approaches such as the Arctic circle. We felt that the Forum could have provided more opportunities for sharing and learning around the diverse mobilising frames used by other movements. Emergent questions include:

- In what ways can food sovereignty or agroecology act as a viable joint framing for systemic convergence?

- What other mobilising frames are used by allied movements that we could integrate, link up with, or better articulate in our collective struggles and actions?

Nyéléni Global Forum / Creative Commons

Fourth, the Forum brought together different organizing and political culturesacross widely different social movements, providing space for global movements (as constituencies) and regions to organize politically. While the overall methodology relied on consultations at both regional level and within global organisations, the articulation of the two was, at times, challenging. The “Nyéléni experience” varied enormously from delegate to delegate, depending on individual regions, global movement affiliations and personal responsibilities. Some delegates were involved in regional meetings only while those who belonged to global organizations or were part of the various organizing committees had more meetings and opportunities to shape the outcomes of the Forum. The diversity and current state of the food sovereignty movements across the regions led to diverse regional processes, discussions and ways of organising. This raises questions such as:

- What levels, spaces and processes are most conducive and critical for mobilising towards systemic transformation?

- Are regions the most appropriate and effective level for movement building and collective action?

- How to articulate constituencies and regions as drivers of collective identity and convergence?

Finally, the Forum represented not just convergence but also an opening up to new categories of activists including academics and researchers, human rights defenders, artists and other constituencies which were recognized as full participants (delegates). This meant that political participation and speaking rights were effectively extended to actors beyond the constituencies that historically make up the core of the food sovereignty movement. For us, this meant that as human rights activists, NGOs and researchers, we were formally recognized as playing political roles in the movement, and not just support roles. This contrasts with the role of philanthropic actors supporting agroecology and food sovereignty who were invited as observers. While we welcome the inclusion of a broader diversity of voices in the fabric of convergence, many questions remain around the role of non-affected constituencies in the movement:

- How can Nyéléni effectively open up while maintaining political control in the hands of social movements?

- How can or should newly recognised delegates from non-affected constituencies (e.g. NGOs, scholar-activists), engage politically and effectively while ensuring the voices of the most-affected remain prioritized?

- Should researchers try to self-organize to better respond collectively to the needs of the movement or should we continue to rely on individual relations of trust and existing connections with different movements?

- How can movements facilitate horizontal dialogue and the co-construction of knowledge and alternatives by a plurality of knowledge holders?

Nyéléni Global Forum / Creative Commons

Looking ahead

After the Forum, the Kandy Declaration was released on November 15 during the People’s Summit as part of the UNFCCC COP 30 in Belém. The Declaration builds on the Common Political Action Agenda (CPAA) and the outcomes of the Forum and identifies the struggles ahead while also showing how our shared histories of struggle and solidarity continue to inspire action. It outlines a collective commitment towards systemic transformation.

To strengthen convergence, the Declaration calls for deepening dialogue with trade union movements, Indigenous Peoples, researchers, solidarity philanthropy and other social movements, while also building collective capacity to radically transform multilateral systems by dismantling corporate control. Some of the joint actions that have been agreed include:

- Solidarity against imperialism, war, conflict and genocides while actively resisting the use of famine and destruction of health systems as weapons of war;

- The organization of an annual Nyéléni day to continue to deepen and strengthen the movement and make our struggles visible;

- A general strike to make visible the central, and undervalued, role of care work in our societies;

- Political formation processes that target topics including popular feminism, anti-racism and more;

- Building new narratives through popular feminist communication and peoples’ communication.

There is work to do. The path ahead is uncertain but we are ready. It is critical to continue to weave together the fabric of convergence to advance systemic transformation: Now and forever.